Using acting techniques as a novelist

How I'm using acting techniques to write characters with purpose, who inhabit physical space convincingly, and who drive the narrative forward 🎭

I’m a big fan of books about the craft of writing, but I also love digging in to books about other storytelling crafts for nuggets of advice that can be applied to story-writing.

One of my favourites in this genre is A Practical Handbook for the Actor1, an acting guide from the 80s which has nothing to do with writing, but has everything to do with embodying a character in order to tell a story.

It’s a fascinating look behind the curtain at what goes into an actor’s preparation, but it also made me hyper aware of what my characters are doing in each scene — because they aren’t just standing there delivering quippy lines of banter.

Scene goals and in-scene actions

Every book about writing I’ve ever read has included some guidance on defining the overarching internal and external goal of a character, but they didn’t necessarily explore how that applies on a scene-by-scene basis. Actors, on the other hand, have to have a very granular understanding of goals and in-scene action in order to bring the story to life moment by moment.

What A Practical Handbook for the Actor teaches us, is that an actor decides on the physical action they will take in a scene. The action is something the character is doing to try to achieve their goal, but it’s more about how they are trying to achieve it. And when picking an action, it must not be an errand, or something that can be accomplished in one line. The action must be something that the character might fail at, so that your audience (or in our case, reader) is kept engaged.

For example, a character’s objective in a scene might be to get information out of another character. But you could imagine a big difference in action if the character was pairing threatening physical action in the scene with a gossipy line delivery — like a friend trying to get them to spill the tea (ie, this almost comes across as quite psychotic, and is very reminiscent of a character like Killing Eve’s Villenelle) — versus plying them with the same tone, but offering rewards to try and entice it out of them (which veers more towards Grease’s “Tell me more, tell me more”).

The objective is the same, but the action is very different.

Uta Hagen and the power of conflict

The other thing the handbook teaches is that, while the action depends on their goal, the goal must have to do with the other character in the scene. This idea that a character’s action is dependent on the other character reminded me of a clip I saw a little while ago of actress Uta Hagen (a member of the original cast for Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?) giving advice on what to discuss with a scene partner upfront.

She said:

“Discuss what your objectives are, and make sure they’re in conflict. Because, if I say ‘my objective is to get you out of here’, and the other one says ‘my objective is to get out’, well then you’ve got nothing to play, right?”

Tension and conflict are so important to writing a compelling narrative, and it’s super interesting to see how this doesn’t need to mean that the characters are fighting (though it can), but that they are at cross-purposes in some way.

So, lessons

The key to a conflict-ridden scene, with compelling tension, lies in specificity: concrete actions and clear objectives. This is what I’m adding to my scene notes:

List who’s in the scene.

For each character, write down what they want in that scene (their objective).

Make sure at least some of those objectives are in conflict. They shouldn’t all want the same thing.

Check that each character’s objective is tied to another character. They should want something from each other.

Make sure each character’s action is something they could fail at. It should take effort and strategy. It must not be an errand.

Think about how the same objective could be acted out in different ways. For example: threatening vs. sweet-talking.

Play with tension — let the conflict drive the scene.

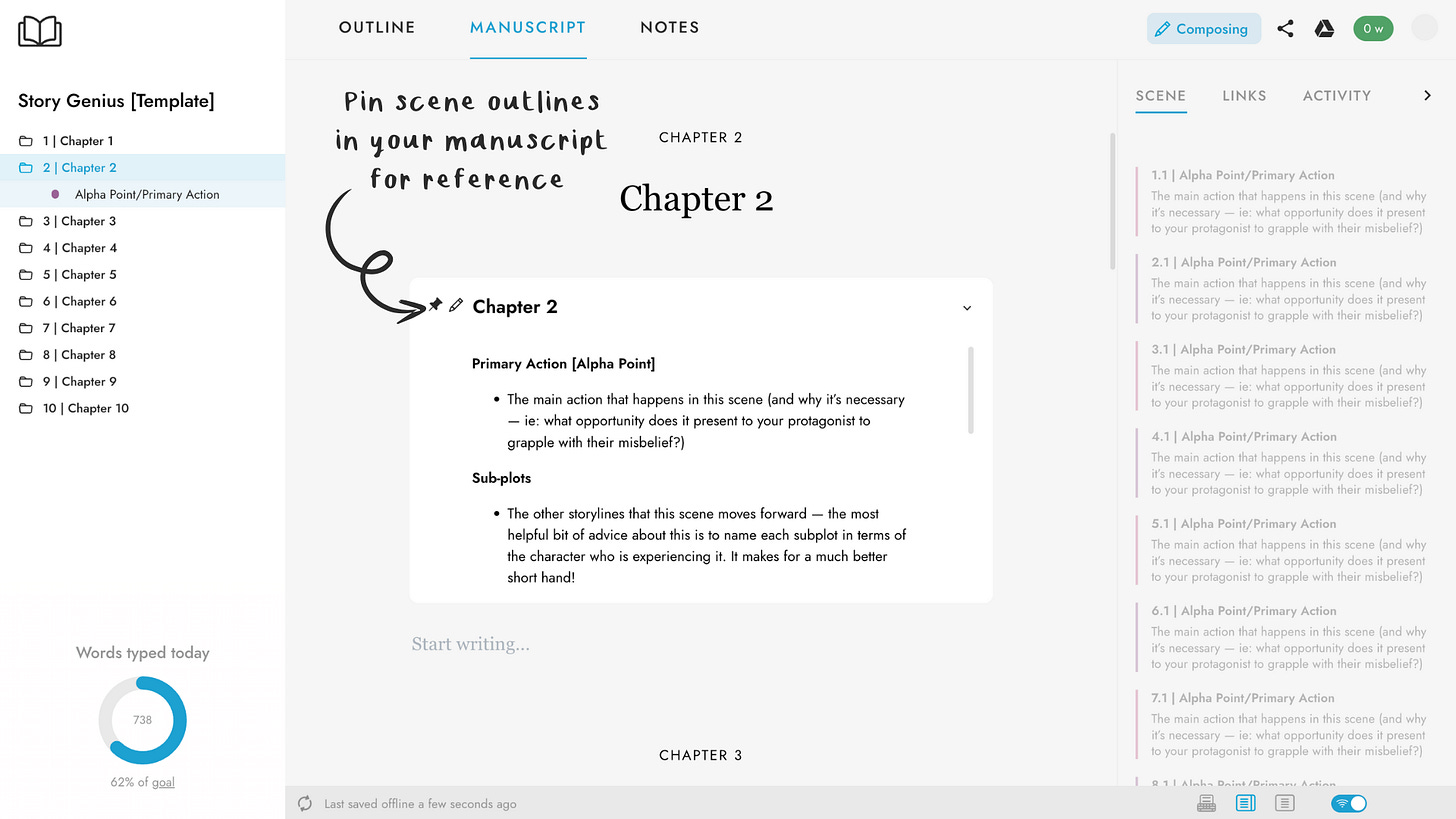

I use pinned scene notes in First Draft Pro to keep track of this while writing:

If you’re thinking of buying this book yourself, please consider ordering it from an independent bookstore! They’re the cornerstone of local literary communities, and deserve our support 💛